Panel 7 : The story of water

Several sources of water were available for the people of Libourne from the very beginning. This included water from the Isle and the Dordogne, water from the numerous springs and streams in the area, and water from wells. The quality of this water varied, and river water in particular needed to be filtered, especially after any period of flooding.

However, over the course of its history, Libourne's supply of drinking water has not been as easy to ensure as first appears. The managed springs and fountains bear witness to this fact.

A/ THE ROUDEYRE FOUNTAIN, A SPRING ON THE OUTSKIRTS OF THE TOWN

The Roudeyre fountain has been used for a very long time. Located banks of the Isle, the spring which feeds the fountain has the benefit of a regular flow of water.

A pool already existed in 1683, but its poor condition required a whole programme of work. The fountain was renowned for the quality and cleanliness of its water, and its location away from the town centre spared it from urban pollution for some time. It was mainly used by the district’s inhabitants, who were few in number at the time, and by sailors who came to buy supplies for their trips in ‘gabarres’ (barges).

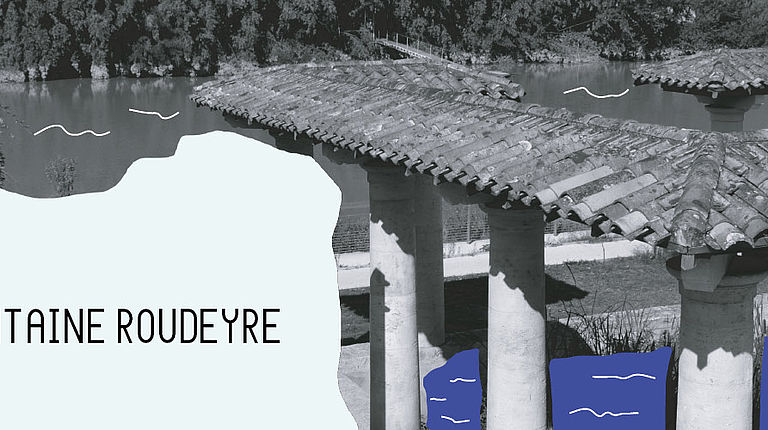

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the authorities regularly intervened to maintain and renovate the Roudeyre fountain. Diverting its water to the town centre was even considered. The renovation work carried out in 1832 gave the pool its present shape and colonnade. The project’s original aim was not to create the Greco-Roman style building we see today. The columns supported a large, tiled roof covering the pool and its outer area. They were reinforced around the edges by walls made of planks. At that time, the building provided shelter for a wash house and its washerwomen. The latter paid a fee to a farmer who operated the wash house on behalf of the town.

This farmer had responsibility for the maintenance and supervision of the water quality and cleanliness of the pools, which he had to empty and clean every day. In particular, he must not, under any circumstances, ‘allow any kind of meat, tripe, fish or other objects of this kind to be emptied into the fountain’s pools, the wash house or the soaking pool.’ Here we can see the extent to which household practices have changed since the 19th century.

As for the wash house, the advent of washing machines robbed it of its usefulness.

Water from the Roudeyre fountain was declared unfit for consumption in 1951. This put an end to age-old practices which had already largely disappeared. At one time threatened with demolition, it was a subsequent restoration in the early 1960s which gave the wash house its appearance we know today.

The Roudeyre fountain, which has become a place for walking and relaxing, still bears witness to the past of an entire neighbourhood: the Quartier des Fontaines. It remains the last example of the many managed streams and wash houses present until the 19thcentury along this section of the banks of the Isle.

B/ WATER WITHIN THE FORTIFIED TOWN

Throughout the Middle Ages, one of Libourne's main water sources was the Font Neuve. This involved a stream whose source is located in the town centre, some 400 metres from the Dordogne. This spring was quickly converted into a fountain. Its water was used extensively for domestic purposes, but was also used by the many butchers and fishmongers in the market nearby. As a result, the stream regularly became unsanitary and the fountain and its drain were rebuilt several times. This work gave rise to the name of the Font Neuve spring (the new fountain).

By the end of the 17th century, the supply of drinking water to Libourne had become a problem. Public wells were sparse and usually polluted. Some were reported to be used regularly as dumping sites. Many of the private wells were subject to groundwater pollution due to human activity.

This gave impetus to the idea of creating a public fountain in the fortified town’s central square to supply all the inhabitants with clean water. It would take more than seventy years for this water source to become operational. There were many obstacles to overcome:

- finding an abundant, drinkable water source, which was finally found at a place called Mandinet (near the current railway station).

- creating an underground conduit leading to the square after passing under the fortifications.

- redesigning the square for the construction of the pool and fountain. This involved the demolition of a wooden hall which had occupied a large part of the area since the Middle Ages.

The project was finally completed in 1770. However, it did not provide the hoped-for solution to the water issue. The conduit was subject to numerous leaks. The fountain’s pool became polluted by rubbish and stagnant water. Cleaning of the pool and numerous repairs to the pipes followed until it was decided to replace them completely.

A new fountain was built in 1832. It was huge and in a square design comprising four arcades topped with a dome. However, in 1874 it was replaced much like its predecessor and for similar reasons.

A supply of drinking water to the people of Libourne was not finally achieved until 1889 with the installation of a network supplying houses with running water and the commissioning of a pumping and water treatment station at Gueyrosse in the suburbs of Libourne, which is still in use today.

The fountain which has been in Place Abel Surchamp since 1973 on the site where other fountains have been built over the centuries is a reminder of the town’s efforts to gain access to water. It is also testament to the fact that just because water is common, it does not mean that it is suitable for household use.