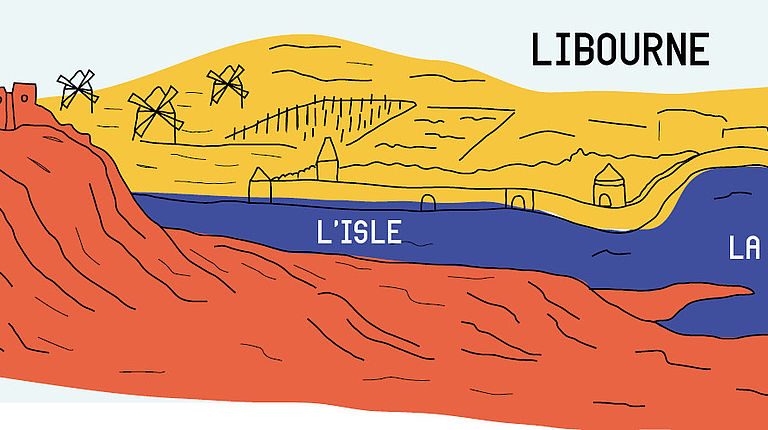

Panel 1 : Geographic meeting point

Château de Fronsac

The knoll in Fronsac was shaped by erosion and the passage of rivers over the region’s long geological history. It became the highest point in the region and therefore an important strategic location. The knoll was fortified in the 8th century by Charlemagne. He had a military base built there with the aim of subduing Aquitaine and Gascony, whose respective dukes were, at that time, leading an almost permanent revolt against Carolingian rule. This stronghold gave its name to the knoll. The name Fronsac is derived from the Low Latin ‘Franciacum Castellum’, i.e. the castle of the Franks. Like Castillon, Fronsac became the seat of an important Viscounty in the following century which came under English suzerainty in 1154.

Together with the fortified town of Libourne, the castle at Fronsac played an important role in defending the northern border of the Duchy of Aquitaine. This neighboured the domain of the King of France, an area which continued to expand until the eve of the Hundred Years' War.

Fronsac was rebuilt in the 13th century and became the focus of much envy. In 1378, Viscount Guillaume Xans de Pommiers was suspected of treason for having wanted to give the castle to the French. After being arrested in Libourne and tried in Bordeaux, he was ‘publicly beheadedin the city of Bordeaux (…) in front of all the people, who were greatly impressed’. However, the death of this treacherous noble, (a member of the high aristocracy of Gascony) was one of the initial reasons for the region’s nobility gradually distancing themselves from English power.

The castle was attacked several times during the Hundred Years’ War. In June 1451, French troops set up campin front of Fronsac. The English governor evacuated the fortress as a result. Two years later, the English, after having regained possession of the area in 1452, were definitively driven out following the French victory at Castillon on 17 July 1453.

After the Hundred Years' War, the Viscounty of Fronsac passed into the hands of various noble families who acquired the title of Duke in the early 17th century. However, most of the time these nobles were absent from the castle and left it in the hands of a governor. It was not uncommon for the castle garrison to engage in acts of banditry and intimidation against the inhabitants of Libourne, who suffered from having the castle so close by. In July 1489, ‘A large stone, weighing 12 pounds or thereabouts, which had been fired from a piece of artillery by the soldiers who were at the time at Fronsac castle, broke a wooden pillar on Micheau Becède’s house’. The town repeatedly demanded justice from the King of France. Royal justice was again carried out at the beginning of the 17th century. Hercule d’Arsilemont, the governor of Fronsac castle who was guilty of numerous misdeeds and acts of cruelty, was beheaded in Bordeaux in 1620. His head was displayed on the gate to the Grand Port, facing the knoll. Two years later, the feudal castle was razed at the request of Louis XIII and to the great satisfaction of the jurats of Libourne.

Nothing remains of this imposing fortress, which covered an area of just over one hectare. The crenellated walls flanked by towers followed the shape of the landscape. ‘The great tower’, mentioned in the 13th century, was intended to guard the entrance to the fortress.

In 1631, Cardinal de Richelieu bought the Duchy of Fronsac, which, although deprived of its main castle, still represented an important area covering 50 km 2 and included 17 parishes.

In the mid 18th century, his heir, Armand de Vignerot, Duke of Richelieu and Fronsac, had a private residence built on the site of the castle. This new château was noted for its architectural qualities at the time of its construction (it included a reception room with a floor made of mirrors) but was demolished in 1793 during the Revolution.

It was not until the 1860s that a new residence was built on top of the knoll. This building, remarkable for its domed lantern, enjoys breathtaking views of the surrounding area and now looks out over a tranquil wine-growing estate.

The Mascaret Viaduct

In addition to its military occupation, the knoll in Fronsac has always been an important thoroughfare, not only because of the considerable amount of river traffic which took place up until the beginning of the 20th century, but also because of the presence of several overland routes. The lack of a bridge over the Isle and Dordogne rivers meant that ferries had to be used until the early 19th century. Since then, they have been replaced by several bridges. Mascaret viaduct is the last of the bridges built over the Dordogne opposite Libourne.

The crossing of the A89 motorway over the Dordogne and the marshlands of the Arveyres peninsula required the construction of 3.5 km of engineering structures, including a 540 m long deck for the Mascaret viaduct. The concrete piles, which are anchored deep in the river bed, support 400-tonne steel beams. They were brought to the site by a self-propelled barge and installed in April 1999 using a crane suitable for lifting such loads. Although the piles rise between 21 m and 34 m depending on the tide level, the viaduct now prevents sailing boats from entering the port of Libourne.

This characteristic definitely marked an end of an era. From 1838 onwards, when the crossing of the Dordogne by a road bridge and then by a railway bridge was first envisaged at Saint André de Cubzac, the authorities in Libourne used all their influence to ensure that the decks of these bridges were built at a sufficient height to allow the passage of ocean-going sailing boats. Pilots from the port were dispatched to ensure that navigational conditions remained the same. It was vital that these ships had access to the port of Libourne, whose trade meant that it had to remain a seaport as well as a river port. The issue, although important then, was much less so in 1999. Today, the port's main activity is no longer commercial, but instead focuses on river tourism and receiving cruise ships.